Renewable energy is booming in the United States—and so are the benefits delivered by these projects. Wind, solar, and battery storage just had their best third quarter ever for new installations. Despite federal and local challenges, all these new projects will soon yield benefits for their host communities.

But are the benefits enough to reduce public opposition, improve community buy-in, and maintain momentum for new infrastructure?

How Communities Benefit from Renewable Energy

Communities benefit from renewable energy projects in many ways: tax revenue, in-kind donations, community benefit agreements, jobs, local economic activity, lease payments to landowners, and road use agreements.

While community benefit agreements are often highlighted as the premier mechanism for delivering benefits, a National Renewable Energy Laboratory analysis of wind energy development found that fewer than half of examined wind projects (205 out of 546) had any formal community benefits. Community benefit agreements with direct payments to local governments were uncommon. In contrast, virtually all utility-scale renewable energy projects contribute tax revenues to host communities.

Additionally, when compared to the legacy fossil fuel industry they seek to replace, renewable energy projects—especially solar and battery projects—generate far fewer indirect economic benefits for host communities. While there are some construction and operations jobs and downstream benefits from development, the primary means of delivering renewable energy benefits to a community is through tax revenues.

Our New Tax Policy Report

To better assess the scale of local tax revenues flowing to communities and to compare different state tax policy approaches, Clean Tomorrow commissioned Strategic Economic Research (SER) to conduct an analysis. The resulting report, “Comparison of Property Tax Treatment for Solar and Battery Storage in Seven States,” analyzes how seven states (Colorado, Indiana, Kansas, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Virginia) treat local property taxes for a hypothetical 200 megawatt solar-plus-battery storage project.

What We Found

The results are illuminating. Here are the highlights:

States take wildly different approaches to taxing renewable energy projects. Across the seven states we studied, no two states taxed renewable energy projects the same way. This variation yields surprising results in annual and long-term revenues. Some states apply standard commercial property tax rules to renewable energy, while others tax facilities based on factors like the energy generated. Even within the same state, revenues may differ significantly across local governments if projects are assessed locally.

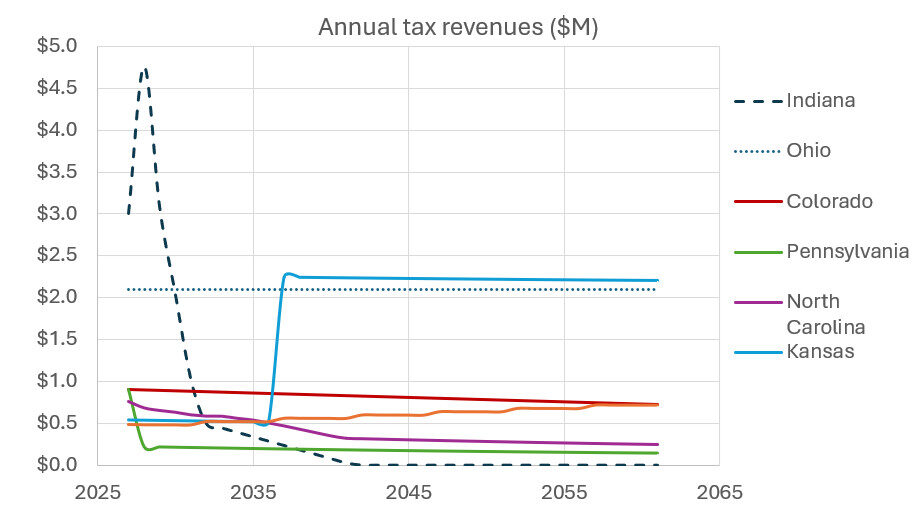

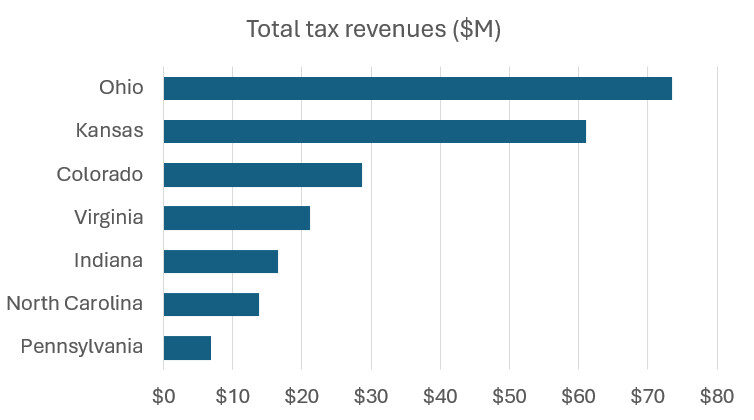

Local tax revenues vary dramatically by state. The potential differences in tax revenue within a state were minor, but the differences in revenue across states, based on tax policy design, are substantial. For example, across a 35-year timespan, the same hypothetical project would generate $6 million in total property taxes in Pennsylvania (the state with the lowest revenues in our study), compared to $73 million in Ohio (the state with the highest revenues). That means a county in Ohio will receive 10 times more revenue than a county in Pennsylvania for a similar project.

How states calculate value matters—a lot. Local tax revenues fluctuate significantly over the life of a project in many states, which may make budgeting challenging for local governments. States relying on standard depreciation generate high near-term revenues but experience sharp declines, while methods like Colorado’s levelization or Virginia’s long schedules smooth revenues over time. Indiana’s recent removal of a valuation floor means far less revenue late in a project’s life. Rollback provisions create added taxes in year one for developers converting farmland, especially in Pennsylvania where the rollback spans up to seven years, but revenues drop precipitously in later years.

Exemptions and agreements can reshape the equation. Kansas and North Carolina offer broad renewable energy equipment exemptions, which may help attract developers and drive competitiveness. However, exemptions tend to yield less revenue for communities and may generate opposition to development over the long term. A Payment in Lieu of Taxes (PILOT) program, like those offered in Ohio and Indiana, allows for exemptions, but backfill local governments with annual payments on a per megawatt basis.

Why This Matters

Renewable energy projects often pay one or more state or local taxes (property tax, production-based taxes, sales and use tax, local income tax), but the tax schemes—and magnitude of revenues—differ immensely between states. Assessments can vary even within a single state. Factors like state and local assessments, valuation methods, classification, rollback provisions, depreciation schedules, abatements, and administrative processes can all affect the amount, predictability, and certainty of revenues for communities and costs for developers.

Our report includes detailed state-specific profiles and a comparative analysis to help policymakers, developers, and communities understand these differences.

What’s Next

This report is an important first step toward understanding the various ways states tax renewable energy projects. The Siting Solutions Project is committed to continuing this research and identifying the most effective tax policies—policies that deliver substantial, predictable benefits to communities while improving the investment climate for project developers.